Here’s what might surprise you about one of the fastest exits in the AI tools space: it had almost nothing to do with the product.

Yosuke Yasuda built Algoage, a sales and marketing chatbot company, at a time when most founders were still figuring out whether chatbots were even a real GTM channel. He sold it in roughly two years for a multi-million dollar figure.

But the speed wasn’t about shipping faster, or finding product-market fit quicker, than everyone else. It was about how he priced the thing.

That single pricing decision set up everything that followed. The 10x headcount growth. The organizational chaos. The one hire that changed everything.

And now, the product he’s building to make sure no founder has to learn those lessons the hard way again. I sat down with Yosuke to unpack all of it, and what came out was one of the most tactically dense conversations I’ve had this year.

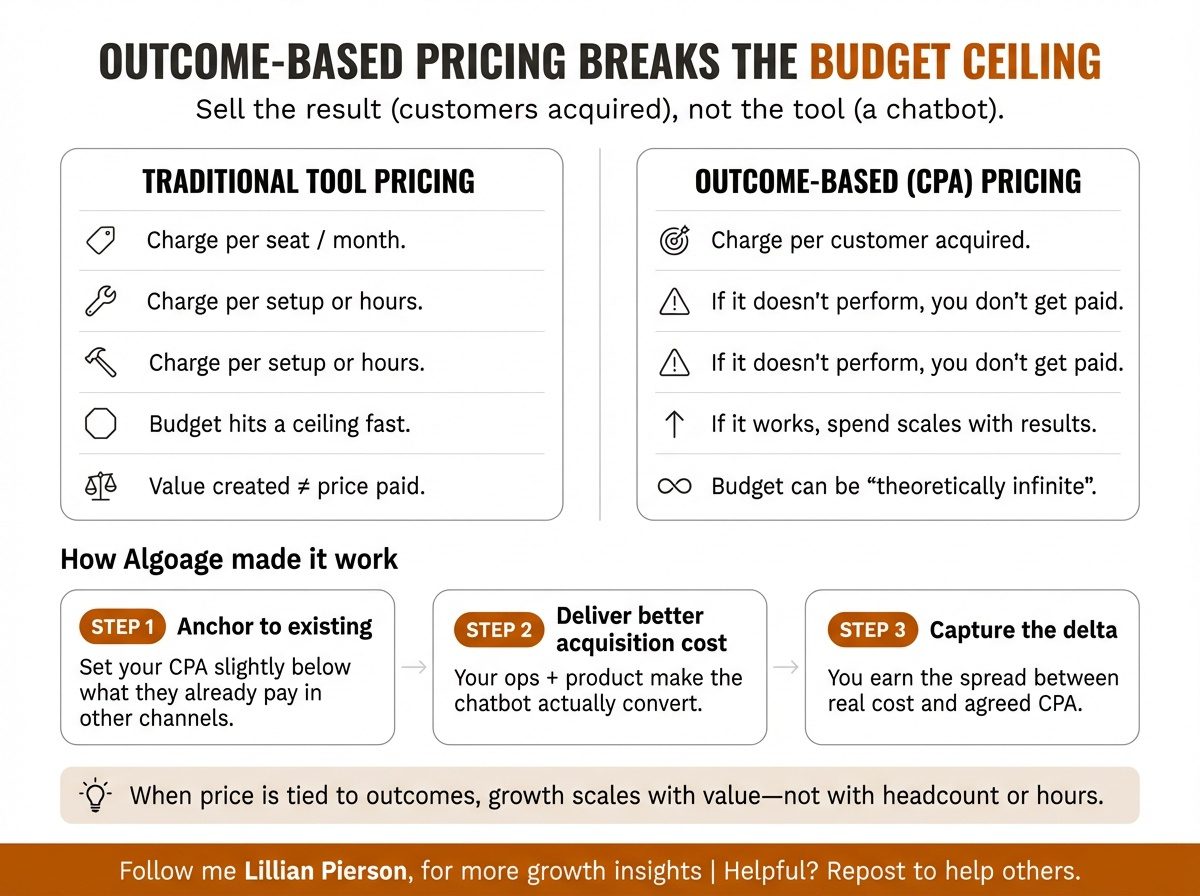

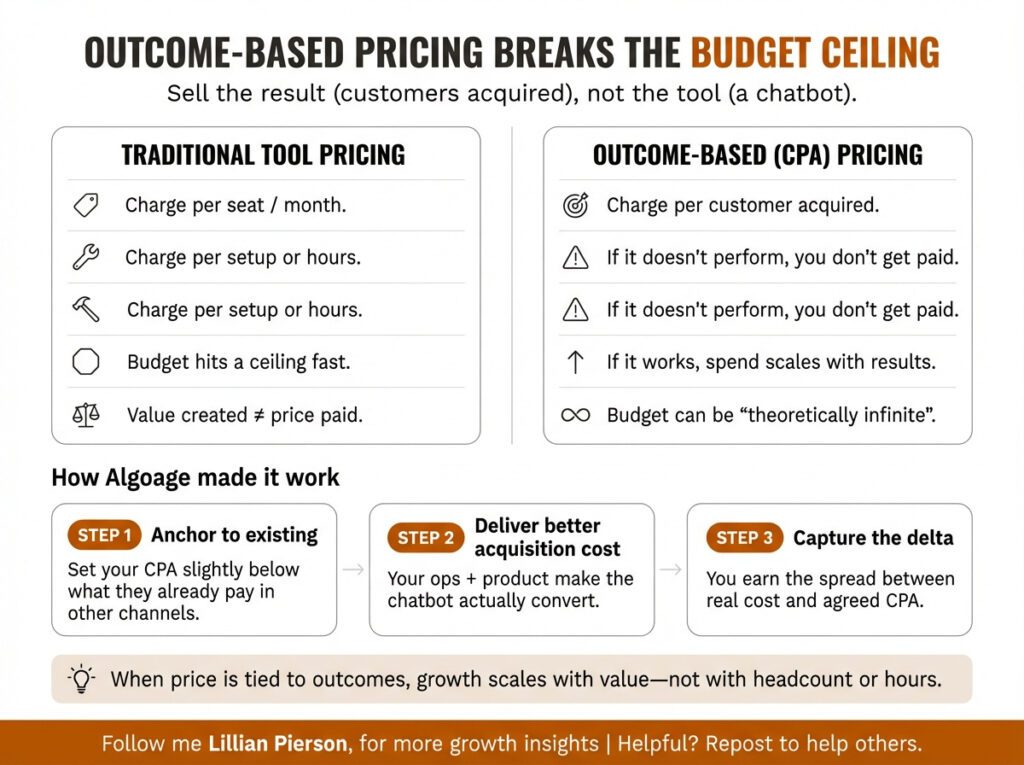

Why Outcome-Based Pricing Breaks the Budget Ceiling

When most people hear “AI chatbot for sales,” they THINK the product is the chatbot builder. You buy the tool. You configure it. You go.

However, that’s not what Yosuke sold. He sold customer acquisition.

Algoage didn’t charge per implementation, per hour, or per chatbot deployed. They charged based on how many customers the chatbot actually brought in for each client. A CPA (cost per acquisition) model, straight from the ad industry.

This sounds simple. It wasn’t. It was one of the highest-risk moves a startup can make – because if the chatbot doesn’t perform, Algoage doesn’t get paid. But Yosuke saw something most founders miss.

If it works, the budget is theoretically infinite.

Think about that for a second. When you’re paying per customer acquired, and each new customer generates revenue for the client, there’s no natural ceiling on what they’ll spend. The pricing scales with the value it creates. That’s not a pricing model. That’s a growth engine.

Here’s how it worked in practice. For each client, Yosuke would negotiate a CPA slightly below what that client was already paying to acquire customers through other channels.

The client saves a little on unit economics. Algoage captures the delta between the chatbot’s actual acquisition cost and the agreed CPA. Everyone wins – as long as the chatbot delivers.

And it did.

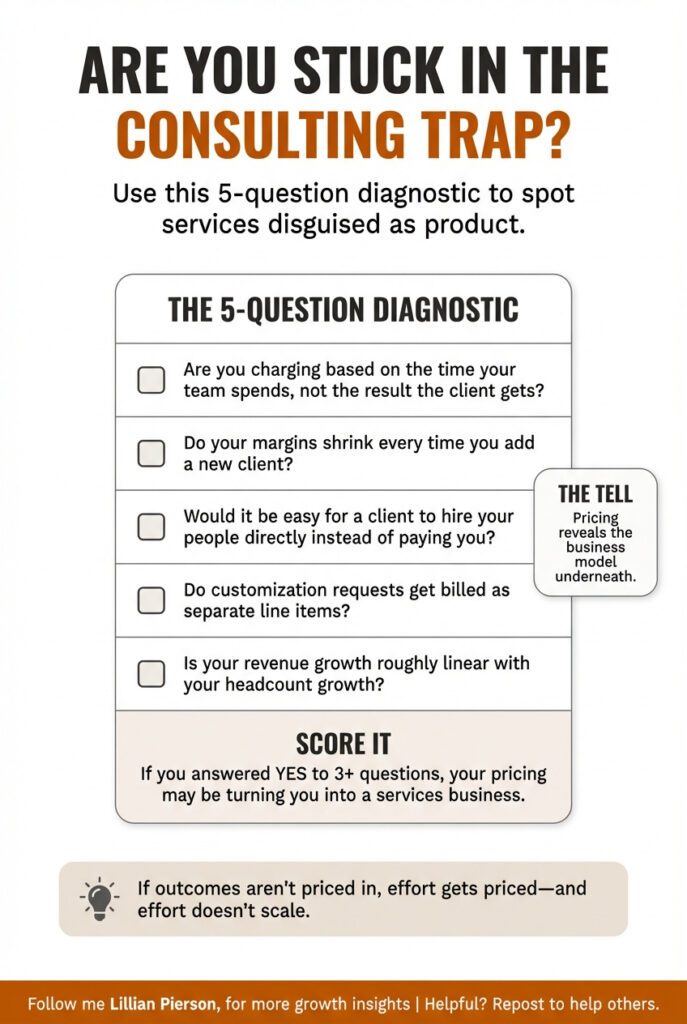

Replicate The Win: The Consulting Trap Diagnostic

Before you dismiss outcome-based pricing as “too risky for my stage,” ask yourself these five questions.

If you answer yes to three or more, your pricing model might be quietly turning you into a consulting firm:

- Are you charging based on the time your team spends, not the result the client gets?

- Do your margins shrink every time you add a new client?

- Would it be easy for a client to hire your people directly instead of paying you?

- Do customization requests get billed as separate line items?

- Is your revenue growth roughly linear with your headcount growth?

The hard part is admitting that most “product” companies are actually running a services business underneath. The pricing model is the tell.

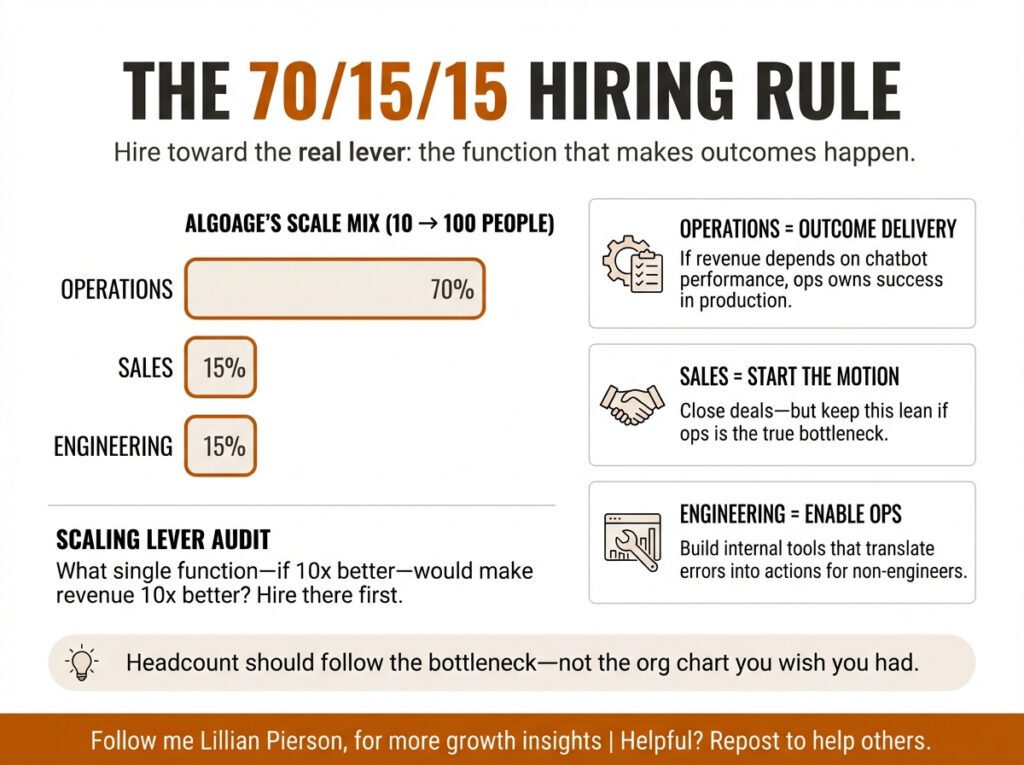

The 70/15/15 Rule: Hire Where Your Lever Actually Is

Here’s a hiring ratio that will make most founders uncomfortable: 70% operations, 15% sales, 15% engineering.

That’s how Algoage scaled from 10 to 100 people in under a year. And it wasn’t a guess. It was a direct consequence of the business model.

Think about it. If your revenue is tied to chatbot success quality, then the single most important function in your company is the team that makes those chatbots actually work.

Not the engineers who build the platform. Not the sales team who closes the deals. The people who deploy, monitor, and optimize each chatbot in production.

So that’s where the headcount went. 70 people, mostly non-technical, running the operation.

But here’s the part that doesn’t get talked about enough… Those 70 people only worked because of what the 15 engineers built for them.

Algoage built a custom product analytics layer in-house. They did it because nothing on the market existed for monitoring deployed chatbots at that time. Google Analytics doesn’t tell you why your chatbot just sent a buggy response to a live prospect.

The real engineering challenge was translating technical errors into language that non-engineers could act upon. When something broke in production, the ops team needed to see exactly where the problem was and how to fix it, without waiting on an engineer to explain it.

In other words, the internal tool was a product. And they treated it like one.

Replicate The Win: The Scaling Lever Audit

Before you hire your next 10 people, answer this: What is the single function that, if it got 10x better, would make your revenue 10x better?

Not your most exciting function. Not the one that feels most “startup-y.” The actual lever.

Then hire toward that lever. Let everything else stay lean. You can always add headcount to sales or engineering later. You can’t easily undo a hiring architecture that was built on the wrong assumption about where growth lives.

Don’t Delegate to Partners. Inspire Them.

Algoage grew partly through revenue-share partner companies – agencies that brought in clients and took a cut. This is a common model in the Japanese ad-tech ecosystem, and on paper it’s elegant. Low upfront cost, outsourced sales motion, shared risk.

It almost didn’t work.

The first version of the partnership strategy was pure delegation. Hand the partners the product information, set up the revenue-share terms, and let them run. Yosuke’s team expected the partners to bring in clients. They didn’t.

So they changed the approach entirely. Instead of delegating, they showed up.

Yosuke’s team started attending every single client meeting with the partners. They explained the product themselves. They showed what it could do. They demonstrated why it mattered. And gradually, something shifted.

Commitment is contagious. That’s Yosuke’s phrase, and it’s exactly right. When the partner sees the founder genuinely excited about what the product does for their clients, that energy transfers.

The partner starts believing it too. And then they start selling it.

The delegation happened later, in stages. Attend every meeting, then co-present, then let the partner present while you listen, then step back entirely. Think: Graduated handoff, instead of one-time drop.

Replicate This Win: The Partner Activation Ladder

If you’re relying on indirect channels (agencies, resellers, integration partners) and they’re underperforming, it’s probably an activation problem. Here’s the sequence:

- Show up first. Attend their meetings. Do the pitch yourself. Let them watch.

- Co-present. You take the lead, they fill in context.

- They present, you support. Flip the roles. You’re the safety net.

- They run it independently. Only after they’ve demonstrated they can close and explain the value on their own.

Warning: Don’t skip steps. The partner needs to absorb the energy before they can replicate it.

The Scaling Wall Every Founder Hits (And The One Hire That Fixes It)

This is the part of Yosuke’s story that I think every founder between 10 and 50 people needs to hear.

Algoage hit 10 people. Things started getting messy. Not in the obvious ways like “we need more engineers” or “sales isn’t closing fast enough.”

It was subtler and more corrosive than that. People were complaining about different things. Two team members would raise issues that were completely contradictory from Yosuke’s perspective.

Meetings filled the calendar. The work happening in those meetings wasn’t making progress – it was just people explaining what they did last week.

This isn’t a people problem. It’s a coordination problem. And the textbook fix – build a management hierarchy – can actually make it worse.

That’s exactly what happened. Yosuke created layers. Managers and executors. Clean reporting lines. Organizational structure that looked right on a slide deck.

It didn’t work. The managers optimized for clean org charts, not for actual progress. They cared about whether the information flow was tidy. They didn’t care whether the business was moving.

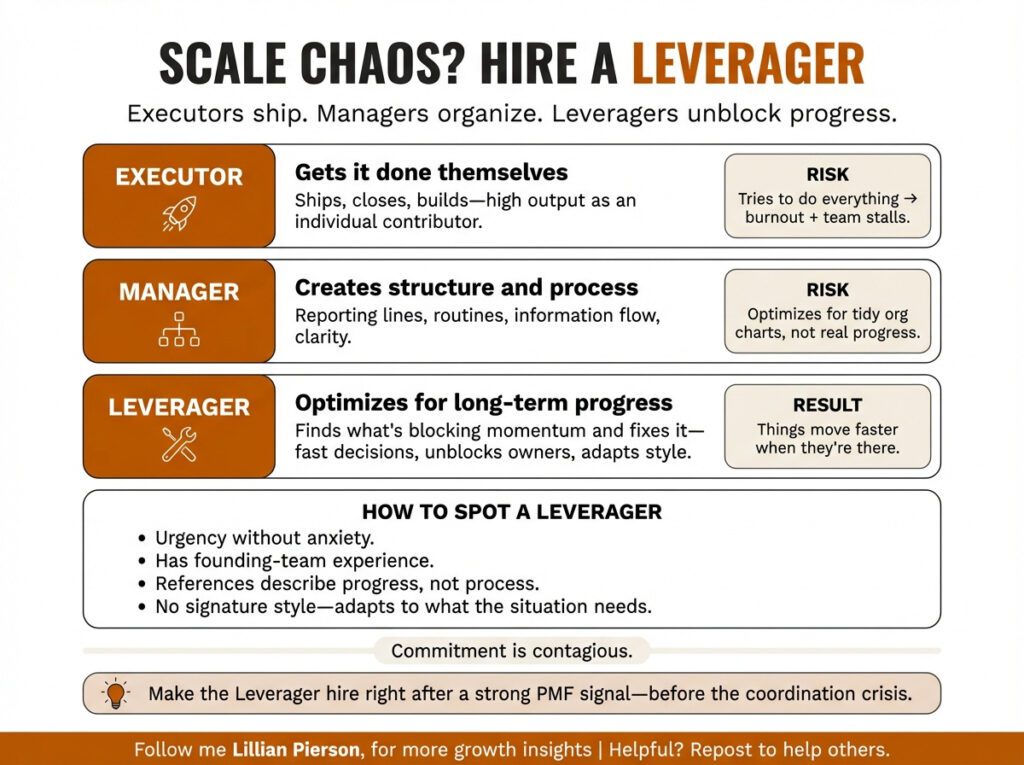

The Three Archetypes You Need to Know

When most people hear “hire a manager,” they THINK it means hiring someone who’s good at organizing people. But there are actually three distinct archetypes at play when you’re scaling, and each is independent.

The Executor is someone who’s great at getting things done themselves. They ship. They close. They build. But they don’t scale. Put them in charge of a team of 70 and they’ll try to do everything themselves until they burn out or the team stalls.

The Manager is someone who’s good at structure. They create clear processes, clean reporting lines, organized information flow. This is genuinely useful, but only if the structure is in service of progress.

A manager who’s disconnected from whether the work is actually moving the business forward is just adding overhead.

The Leverager is the one almost nobody talks about. This is the person who instinctively focuses on long-term progress above everything else. They don’t care about management best practices. They don’t try to do it all themselves.

They figure out what’s actually blocking the business from moving, and they fix that. Whether it means making a quick decision, unblocking someone else, or letting a slow thing play out because it matters more in the long run.

Yosuke hired one. An operations manager with both founding-team experience and later-stage management experience. And this person’s approach spread through the organization because he demonstrated it. Other managers watched, saw it working, and started doing the same thing.

Commitment is contagious. That phrase keeps coming back because it keeps being true.

How to Spot a Leverager Before You Hire Them

This is the part Yosuke flagged as the hardest piece – and I’ve asked him to send me more detail for a future issue. But based on what he shared, here’s what to look for:

- They have a strong sense of urgency. There’s a difference between someone who moves fast because they’re stressed and someone who moves fast because they genuinely care about outcomes. The Leverager is the second type.

- They have founding experience. Not just management experience. They know what it feels like when the whole thing is on the line. That context changes how they make decisions.

- Their references talk about progress, instead of process. When you call their previous employers, ask specifically: “Did things move faster when this person was there?” Not “Were they a good manager?” Those are different questions.

- They don’t have a signature management style. They adapt. Sometimes they jump in and do the thing themselves. Sometimes they step back and let someone else own it. The decision is always driven by what the situation needs, instead of by what feels like “good management.”

If you’re at 10 to 15 people and you haven’t made this hire yet, it’s probably the single most important thing on your to-do list.

Yosuke’s one regret when I asked what he’d tell his 2018 self was immediate and specific: hire the Leverager as soon as you see a strong PMF signal. Don’t wait for the crisis. The crisis is too late.

What Comes Next: Sharick and the AI Chief of Staff

Everything Yosuke learned at Algoage – the outcome-based model, the scaling wall, the Leverager hire, the organizational chaos that eats founder time alive – he’s now trying to encode into a product.

It’s called Sharick. Here’s the problem Sharick is built to solve. You know that feeling where you have 47 things happening at once, and your brain is trying to track all of them, and the reactive stuff keeps jumping to the top of the pile even though the important stuff is what actually needs your attention?

That feeling is what Yosuke calls the organizational chaos tax. It’s the invisible cost that drains founder agency every single day.

Sharick integrates into your email, your Slack, your communication channels. It reads what’s happening across your organization in real time. And then it does something deceptively simple: it helps you figure out what actually needs you right now, and what doesn’t.

If something urgent comes in, Sharick flags it and routes it to the right person – or to you, if you’re the right person. If it’s a low-priority to-do that can wait, it gets deprioritized.

You stop carrying the cognitive weight of tracking everything. The tool does that part.

Yosuke’s reference point for the long-term vision is the movie Her. Not in a sci-fi way. In a “what would it actually feel like to have someone you could dump everything into, who understood your context, and who proactively told you what mattered most” kind of way. That’s the experience he’s building toward.

Right now, the ICP is teams of around 50 people – the exact size where you’ve probably hit PMF, you’re growing, but you haven’t yet built the coordination infrastructure to keep up with that growth. The sweet spot of high frustration and high growth signal.

Sharick is launching in March 2026, and Yosuke is currently prioritizing product validation over distribution right. He wants to make sure it actually works before he introduces it to his network.

The GTM strategy, when it kicks in, will be product-led. Think Calendly. Think Superhuman. You use it, someone else sees it, they want to try it too. The network effects are built into the product itself.

If you want to follow what Yosuke is building, follow him on LinkedIn. Sharick’s landing page is coming soon – I’ll link it the moment it’s live.

P.S. I was actually living a smaller version of Yosuke’s problem the same week we talked. I was building a LinkedIn course on GPT apps, and in the process I built a custom GPT that pulled in my calendar, my stated priorities, and my project management board.

It mapped out my day: two hours of deep work on the thing that actually matters, delegate this to my VA, push this to tomorrow.

I’d only run it for one day when we spoke. But it had already helped me make progress on something I’d been putting off for weeks because I genuinely felt I had no time.

That’s the thing Yosuke is building, but for teams. And if you’ve ever felt like you’re too busy to do the work that actually moves your business, you already understand why it matters.

If you found this useful, forward it to a founder friend who’s between 10 and 50 people. They need this more than they know.

And if you’re not yet subscribed to The Convergence, this is your sign.